Here’s what I knew about copyright as a traditionally published author: I sold my book to a publisher. I signed a contract that gave them permission to sell my book for the lifetime of the copyright.

As an indie publisher, however, I’ve learned to respect my copyright and protect it. Copyright IS my business.

Copyright means that the government protects creative works from the moment they are created. No one may copy your work without your permission, and you’re protected legally for your lifetime plus seventy years. While not required for protection, registering your creation with the copyright.gov office gives you certain legal protections, and I make it a practice to register everything.

Why does this matter? Because copyright has an almost unlimited number of rights which may be licensed. Each license can and should bring the author money or other compensation.

Selling v. Licensing

“Selling” your book to a traditional publisher is actually “licensing” the copyright under the terms of the contract. Most traditional publishing contracts today want as many rights as possible, including worldwide, in all languages, for ebooks, paperback, hardcover, audio rights, dramatic rights, Braille, sub-rights, etc. Merchandising rights are often included as well. Some contracts refer to “any means of communication now in existence or hereafter devised.” Contracts also specify the income splits for each of these rights. Most publishers only exercise a fraction of the licenses that they contract.

Indie publishers, however, prefer to consider each right separately as a potential income source. Indie author and publisher Dean Wesley Smith describes copyright as a Magic Bakery. He says authors should fill up the bakery with as many tasty pastries and breads as possible (stories). Then, slice each pastry into as many slices (licenses) as possible. An indie publisher might not exercise every license either, at least not right away. But the licenses are always available.

One story may be licensed in multiple formats: first digital rights, book club rights, audio rights, merchandise, gaming rights, textbook rights, movie rights, German audio rights, Japanese paperback rights, Swedish ebook rights, nonexclusive anthology rights, and so on. You define what a licensor can and can’t do and the terms of the license, and the territory in which they can sell. The contract includes the money offered for the rights and the limits to the rights.

For example, you might license the right to display a story on a website for XXX days for $XXX. (I’ve done this!) You can add in limits, too. You could add in that the license is for up to 100,000 website visitors. After that, they must pay you $xxx/1000 viewers. It’s all negotiable.

If a certain format is licensed for a limited term—perhaps its only licensed for three years—then it can be re-licensed in that format many times over the lifetime of a copyright. When new formats are devised, those rights are available to license as well. For example, StoryBundle.com creates story collections to sell for a limited time period such as eight weeks. Bundling rights such as this were unknown until just a few years ago.

In the last few years, I’ve licensed bundle rights, Korean rights, Chinese rights, and licensed two picture book texts (art not included) to a website. This is a different way to “sell” a book. Instead of looking for individual buyers, indie publishers look for someone who will license the right to sell to the reader. It’s a volume sale that makes sense.

Beyond that, everything created by a story could be licensed. Characters, setting, and images (if illustrated).

Characters: Think of Marvel Universe’s action figures.

Settings: Disney now owns the Star Wars universe, and is producing more movies in that milieu.

Images: Hello, Kitty! has had books published, but her million-dollar licensing program depends mostly on her image. (For more, see the NETFLIX series: The Toys That Made Us, Season 2, Hello Kitty.)

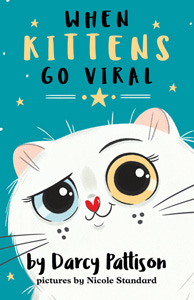

In my case, for the KittyTubers series, I could license rights to the character Angel Persian, t-shirts with Angel’s image, stickers with Angel’s image, the setting of Kittywood, and much, much more. Will everything get licensed? No. But it WILL license SOME of these.

Copyright Extends Your Lifetime Plus Seventy Years

A second important thing about copyright is that it’s valid for a long time. In the U.S., copyright extends the creator’s lifetime plus 70 years. When you create a story, it is protected for the entire length of the copyright. Unless a book is a runaway best-seller, traditional publishers may only exercise the rights for a short time of five or ten years. Out-of-print books, however, still have a life, if you choose to exercise it.

Priscilla Presley closely monitors and licenses Elvis Presley’s copyrights! That includes the personality rights to do Elvis impersonations. It’s brought her a small fortune.

Considering the longevity of a copyright changes the perspective. Perhaps, the best time to market a story is five year from now. Or twenty-five years from now. Or even seventy-five years from now. Smith says it this way: traditional publishing says that books have a shelf-life and then they spoil like bad fruit. But if you consider that the copyright for your story lasts your lifetime plus seventy years, the expiration date is extended. Indie publishers say that the copyright keeps the story fresh and commercially viable for decades. Maybe it needs a new title or a new cover. Or maybe it will sell best in a different format such as a graphic novel or on a website.

As an indie publisher, I’ve learned a new respect for copyright. For more on copyright, read The Copyright Handbook: What Every Writer Need to Know, NOLO Publishing. (Get the most recent edition; if you’re reading this after December 2020, the Fourteenth Edition will be out.)

Caption: When you’re old and your days on Earth are almost done - your copyright is a baby! It’ll live 70 more years!